Platform, curated by Tobias Ostrander, the Estrellita B. Brodsky Adjunct Curator, Latin American Art at Tate, London, is dedicated to large-scale installations and site-specific works under the theme of Monumental Change.

In recent years we have seen the dismantling, defacing, and replacement of public monuments as a central tactic to decolonizing strategies that look to challenge the glorification of figures and events related to histories of slavery and racism, the attempted extermination of indigenous populations and appropriation of their lands, and the subjugation of women.

These displaced monuments have traditionally been sculptural and figurative in style, depicting their subjects in portrait or allegorical formats. The 2022 Platform section of The Armory Show addresses how these recent revisionist practices, which are part of dramatic cultural shifts occurring throughout the world, are influencing artists’ engagement with sculptural form. The selection seeks to raise questions about how contemporary sculpture and large-scale installations might tell historicizing narratives. It asks: What subjects might we collectively look to venerate now? With which materials? And in what form?

Many of the works presented engage aesthetics historically associated with monuments in critical ways, others celebrate personal subjectivities as counterpoints to grand political narratives. Additional projects use soft or ephemeral materials as anti-monumental gestures, while still others look to specifically present women and nature as subjects deserving honor and commemoration.

-Tobias Ostrander

Iván Argote

Presented by Perrotin

In theorizing a new future for historical monuments, Iván Argote deploys multiple tactics that include disappearance, eroticization, natural decay, and fiction. With his installation Wild Flowers, the Paris-based Colombian artist presents planters made from disembodied fragments of Wall Street’s iconic George Washington monument. Scattered across a base of concrete blocks, Washington’s torso, hands, and feet are hollowed out and reimagined as containers for regional plants and flowers as a mode of fostering replenishment and regeneration.

Carolina Caycedo

Presented by Instituto de Visión

Honoring previous generations of Latin American and Latinx women artists, Muyeres en mi is made using clothes sourced from Caycedo’s immediate family and female colleagues. Across these textiles, the artist has embroidered, in a graffiti and activist-inspired typographic style, the names of artists who continue to inspire her, creating a personal historiography of women and art of the Americas. Monumental in scale, while structurally pliable and fluid, the piece allows each of the garments from which it is made to continue to be worn or interacted with in playful ways, such as a cape or “parangole.” Nourished by her experience as a Colombian artist working in Los Angeles, this work forms part of her extensive feminist and ecological political engagements, which centralize historical memory as a fundamental element in fighting perpetuations of violence against both human and non-human entities.

Sonia Gomes

Presented by Mendes Wood DM

Material choreographies in space, Sao Paulo–based artist Sonia Gomes’ work symbolically binds together diverse cultural movements and traditions that are intrinsically linked to the affirmation of memory, identity, and the transformative power of creation in situations of vulnerability and invisibility. Through the use of colored fabric, thread, and found and gifted objects, her multi-dimensional structures stand as insistent placeholders for the absent or unseen body. These gestural inquiries refer to the free movement of the body as a way to decolonize the past and reclaim the present, to reconstitute and celebrate both the self and the artist’s Afro-Brazilian heritage.

Trenton Doyle Hancock

Presented by Hales and James Cohan

As the centerpiece of the Houston-based artist’s expansive solo exhibition Mind of the Mound, Critical Mass, presented at MASS MoCA in 2018, this gigantic, interactive work served as both a promotional icon for the project and as a monument to the artist’s subjective, self-referential mythology involving his characters the “Mounds.” Developed over the past two decades, this generative fiction was initiated as a way for the artist to process his experience as an adult who loves toys, cartoons, horror films, and adventure parks, while also being deeply invested in art historical references, such as the paintings of Philip Guston, or the prints of Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier, combined with the particular excitement he experiences visiting museums. The multi-faceted narrative that has emerged involves portraying the life, death, and dream-like states of these characters and their aggressors, “the Vegans.” This particular Mound is represented as a tent made from black and white striped faux-fur, and covered with pink “sores” that possibly reference traumas that have been tamed through being aestheticized. The fiberglass head that adorns the structure speaks to figurative icons used within fast-food chains or entertainment centers to announce entrances into fantastical worlds. One is encouraged to visually enter this enclosure, experience the animated video presented inside, and examine the root armatures from which Mounds are made.

Juan Fernando Herrán

Presented by PROXYCO Gallery

Presenting empty large-scale sculptural bases that reference historical designs, Héroes Mil reconsiders the traditional logics of monuments as they relate to the desire for national heroes within the history of Colombia. The piece addresses historical memory and how the country sought to cement its Republic in symbolic terms during the celebration of the First Centennial of Independence in 1910. During that year, a large number of monuments were erected throughout the country in an effort to affirm its national identity, and as an attempt to move away from the wounds of the prolonged civil violence known as the Thousand Days’ War. The majority of these monuments were made in Europe, and their transport and installation involved extensive economic and logistical effort. Produced in 2015 during another historical period—in which Colombia was questioning how to publicly heal after recent decades of violence—Herrán’s installation emphasizes the significant absence of deserving contemporary heroes to commemorate, while concurrently—through presenting each base as the wooden scaffolding used to pour concrete in the construction of new monuments—keeping the future potential for such possibilities open.

Roberto Huarcaya

Presented by Rolf Art

Presenting the vulnerable format of a photogram at a monumental scale, Peruvian artist Robert Huarcaya pays homage to the Amazon Rainforest through a process whereby this natural environment produces a photographic representation of itself. Shot at night in Bahuaja Sonene, a Natural Reserve in the Amazon jungle of Peru, this piece involved positioning a 90m long photosensitive paper in a snake-like manner through the jungle’s dense foliage. Its forms were then projected onto the paper through the aid of a small flash and the light of a full moon. The photographic images were developed using the water of a nearby river, which added mineral sediments and pigments to the surface of the work. The artist takes inspiration from a phase written by the 19th century inventor of photograms, William Henry Fox Talbot, which describes how with this medium “nature draws her own picture.” In its references to self-representation, Amazogramas nods to how recently in several Latin American countries the forest, and the Amazon Rainforest, in particular, has been recognized by governments as a living “being,” and deserving of political rights and representation.

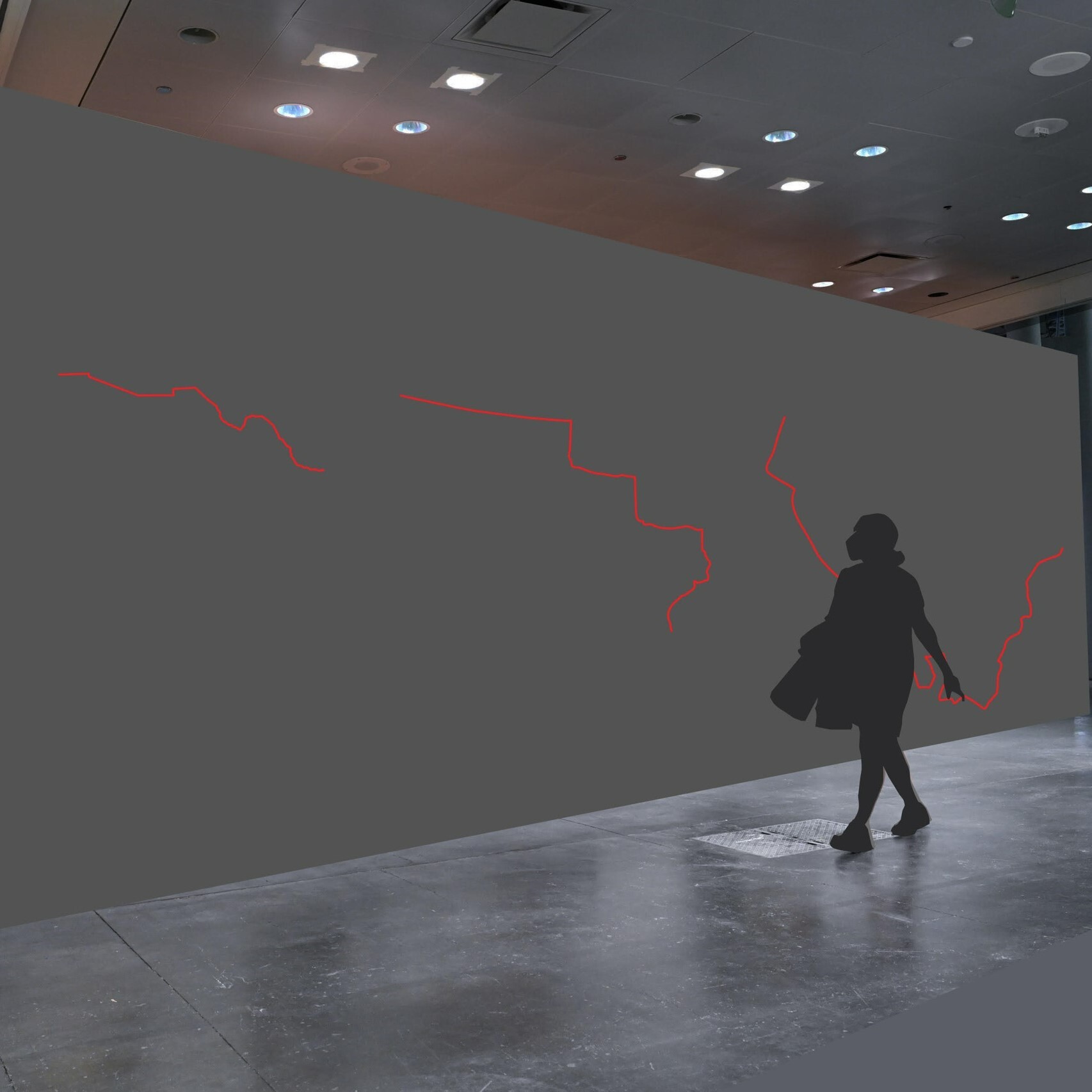

Julio César Morales

Presented by Gallery Wendi Norris

The stability of the US/Mexican border as a monument to the United States’ autonomy and control within the North American continent is challenged in the light installation titled La Línea by Phoenix-based Mexican artist Julio César Morales. It addresses the selective omission of histories in the southwest region of the United States, depicting how boundaries and land ownership have changed dramatically over hundreds of years. The installation consists of four simplified line drawings rendered as red neon sculptures that represent the 1,954-mile border between the US and Mexico. The first sculpture presents the original boundary in 1530, before the arrival of Europeans, spanning from the Cocopah Tribe in present-day California to the Karankawa people in present-day New Mexico. The second sculpture, entitled 1845, is based on the year just prior to the Mexican-American War when territorial boundaries shifted significantly. The third neon, entitled Today, represents the border in 2022. The fourth sculpture imagines a future border, one following a civil war in the US, leaving the states of California and New Mexico independent with open borders to the south. La línea collapses time and space, positioning the border as a main character within histories of power, land, and colonial narratives.

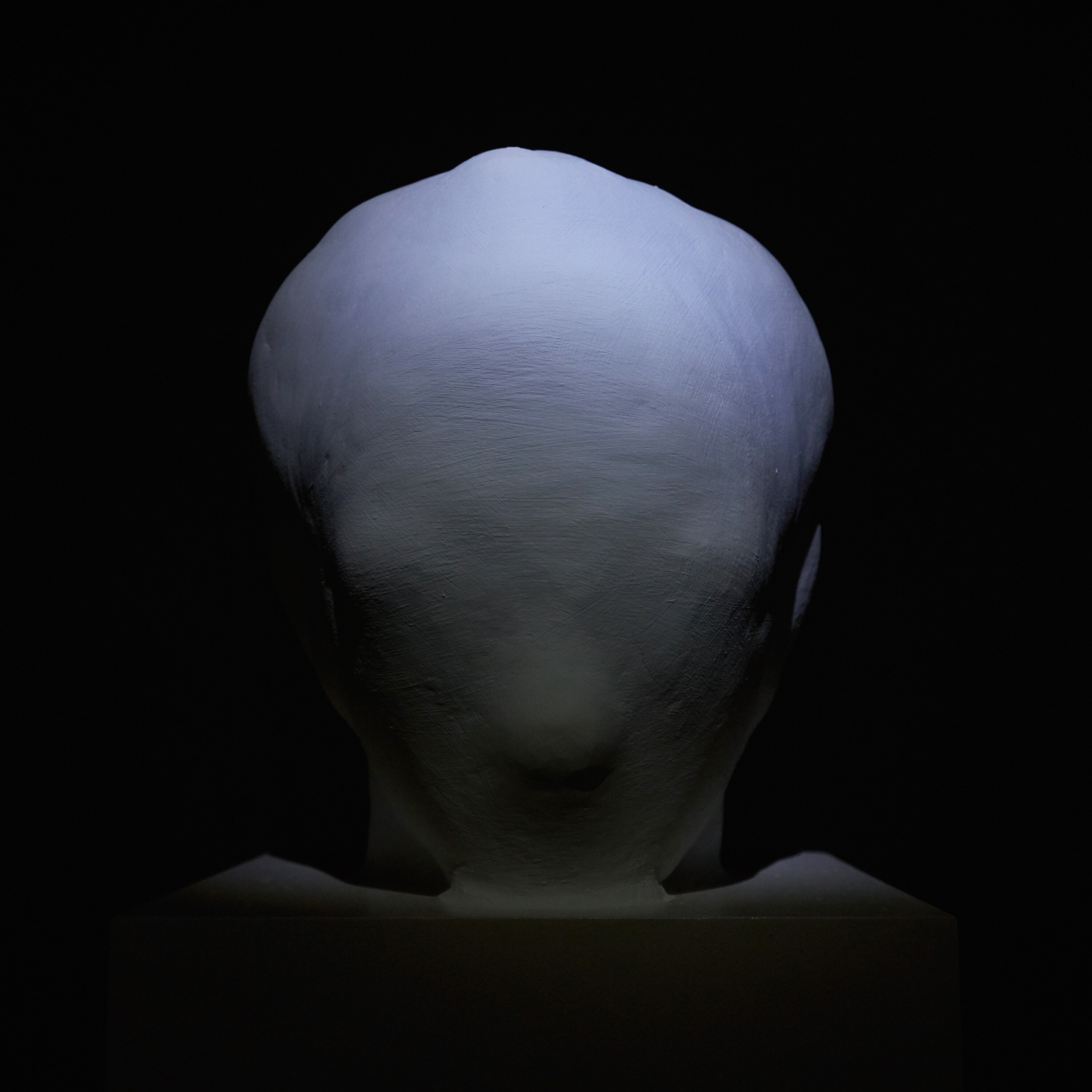

Reynier Leyva Novo

Presented by El Apartamento

This large-scale figurative sculpture is based on the statue of Cuban independence hero José Martí, created by sculptor Juan José Sicre in 1936 for Havana's Plaza Cívica, which was renamed Plaza de la Revolución in 1961. The piece reproduces at original scale the sculpture’s head, which the artist has then covered with 365 layers of paint. In Cuba, public monuments are periodically repainted as a gesture intended to refresh, update, and honor the subjects depicted. With his exaggeration of this act, the artist blurs the features of this figure’s face to the point of unrecognizability, resulting in an uncanny and alien-like representation. The piece addresses the habitual re-interpretations of the significance of Martí and other national heroes within the ever-shifting political context of contemporary Cuba, and how the use of monuments as symbolic capital on the island forms part of the propaganda systems of exclusion, censorship, and ideological control.

Ebony G. Patterson

Presented by Monique Meloche Gallery and Hales

Commissioned for the 2021 Liverpool Biennial, this sculptural tapestry resembles a peacock, whose expansive tail transforms into a garden landscape. This complex piece is inspired by poet Édouard Glissant’s notion that “landscape is our monument,” referencing the need to recognize and honor how the physical landscapes of the Caribbean and other colonial territories are the result of the traumatic labor of enslaved peoples. Patterson’s research centered around Hope Botanical Gardens in her native Kingston, Jamaica. The installation’s grandiose scale and rich symbolism reference the colonial past of this site as a former British Plantation and highlights its historical relationship to contemporary disenfranchised, working-class communities. The artist considers gardens as spaces of both beauty and burial, serving as postcolonial symbols of pasts that are never fully buried nor completely visible. Her distinct style incorporates plastic ornaments, bead macramé, clay flowers, and other materials that symbolize empire, royalty, and diaspora within previously colonized populations. The addition of conch shells with gold leaf appliqué pays homage to the shells that slaves placed on memorials to their dead. Color and tactile materiality function as a blanket-landscape placed over transparent figures, personifying images of death and burial, commemorating invisible bodies lost.

Nyugen E. Smith

Presented by Sean Horton (Presents)

Monuments to human ingenuity in the face of political and environmental catastrophes, Nyugen E. Smith’s totem-like sculptures reference shelters built by displaced migrants, refugees, and hurricane survivors. They are models of bricolage houses constructed using whatever resources can be found at hand—what families manage to bring with them, scavenge for near camps, or find left after a natural disaster. These Bundlehouses speak to the capricious circumstances, tenuousness, and overall fragility of both life and home within the contemporary world. The artist’s diverse practice examines universal experiences of memory, trauma, and spirituality within the multifarious impacts of colonialism on the African diaspora. Informed by his personal history as a first-generation Caribbean-American born in Jersey City, New Jersey, to Haitian and Trinidadian parents, Smith’s works seek to connect past upheavals with present political struggles.

Mary Sibande

Presented by Kavi Gupta

As a gesture toward monumentalizing herself, with this sculpture we see Sophie, artist Mary Sibande's avatar, stepping up onto a pedestal. She wears a purple Victorian-style dress that recalls the aesthetics of the British Colonial Empire. Representing this persona’s purple phase, the color addresses the spirit of constructive resistance encapsulated by the Purple Rain protests in South Africa during apartheid, during which authorities sprayed protestors with purple ink from water cannons, intent on marking them and making them easier to arrest. Hundreds were indeed rounded up and jailed, yet protestors commandeered one of the cannons and turned it on the governing party’s legislative offices. After the riot, graffiti around the city foretold, “The purple shall govern.” Purple is also a reference to clergy and royalty, two authoritarian forces in colonial Africa. Here, Sophie has adorned herself in purple garb, as she ascends with dignity into her new role. Beneath her purple clothing, we can see hints of her next phase, the red phase. For Sibande, red expresses the contemporary frustrations of Black South Africans, a chromatic choice stemming from the Zulu aphorism, “ie ukwatile uphenduke inja ebomvu,” meaning “he is angry, he turned into a red dog.” The artist not only addresses the many faces of herself and Sophie in this work, but also the complex personhoods of all African women who continue to create worlds and narratives outside of the canon of Western Imperialism.

Sean Townley

Presented by Night Gallery

Across his practice, Los Angeles–based artist Sean Townley subverts the rhetoric of progressive democracy in order to gesture toward the imperialist authoritarianism and ritualism that pervades contemporary political life in the United States. His large-scale Gassing the Imperial Throne is centered around a wooden throne that has been sealed within a clear, custom-fabricated plastic bag. The throne, likely a replica of a bishop’s seat built for an ecclesiastical setting, is flanked on either side by tanks of argon gas, a conservation material used to remove insects and microscopic life from aging wooden artifacts. The throne itself is adorned with a double-headed eagle, a historical symbol of empire and nationalistic unity. The heads of the two eagles have been removed by the artist, an intervention that problematizes the notion of patriotic allegiance. As Townley enshrouds the throne and the decapitated emblem with argon, the artist effectively “gasses”—replacing oxygen in the air with a noxious compound—these ceremonial and politically-charged objects. By literally inducing anoxia, Townley symbolically destabilizes the hierarchical power and sacrosanctity of contemporary imperial manifestations.